Introduction

Although economists are predicting a gradual recovery of the U.S. economy beginning sometime in the third quarter of 2020, forecasts show that the labor market will not return to pre-pandemic levels until the end of 2022.1 In Massachusetts, where unemployment is significantly higher than the national rate, it could take even longer to recover all of the jobs lost during the COVID-19 recession due to the initial severity of the pandemic and the exposure of key industries like education and health care. Against this backdrop, residents face reduced unemployment insurance benefits that will constrain their ability to continue making their housing payments in full. Coupled with the eventual expiration of state and national eviction moratoriums, the cumulative impact of deferred rental and mortgage payments has the potential to lead to large increases in housing displacement in 2021.

In the low-income housing market, renters in particular struggle to access and maintain quality housing that has become increasingly unaffordable over the past several decades in many Greater Boston communities. Cost-burdened, they end up vulnerable to eviction and displacement and segregated into areas and neighborhoods of concentrated disadvantage.2 The COVID-19 pandemic has not only exacerbated the vulnerabilities of low-income households, but also those of the existing housing system, which threatens to collapse under the large and unanticipated shock to household incomes. Widespread job loss means that many are unable to fully pay rent, which has the potential to displace tenants—and smaller landlords too, who account for a disproportionate share of the affordable housing market. This disruption to the affordable housing ecosystem could result in a shift in ownership towards institutional investor landlords who are more likely to raise rents and have a higher propensity to evict tenants once the moratoria expire. The consequences for housing instability are likely to be more dire in urban areas and communities with high concentrations of people of color throughout the Greater Boston region, where both the health and economic impacts of the COVID-19 crisis have been particularly acute.3

About the Series

With the rapid changes in the economy and the housing sector driven by COVID-19, the Greater Boston Housing Report Card partners have transformed this year's report into a series of webinars and accompanying issue briefs during the second half of 2020. This is the second report in the series.

Author for this Brief

Alicia Sasser Modestino

Research Director

Dukakis Center for Urban and Regional Policy

Absent intervention, the COVID-19 pandemic could result in dramatic changes in the lower-priced housing market, with tragic, irreparable consequences for low-income households of color in Greater Boston and across the nation. Public officials have acted accordingly, implementing short-term policies and programs to prop up the market through the immediate phase of the crisis. But it is important to note that, even though the pandemic precipitated these immediate challenges, it did so in part because of the market’s underlying failures and inequities. Many of the interventions undertaken by cities and states in response to the economic disruption caused by COVID-19 can also serve to reduce these imbalances. This creates a unique opportunity to learn whether, how, and to what degree such policies are effective, and can provide the basis for redesigning the naturally occurring affordable housing market to be more equitable and, in turn, more resilient to future crises.

What is the current economic outlook for the nation and the region?

With the stock market returning to record highs,4 national economic forecasts indicate that GDP will rebound in the third quarter, followed by continued economic growth of 4 to 5 percent per quarter through the rest of 2020 and into 2021.5 The latest state forecast from MassBenchmarks indicates that economic growth across the Commonwealth will experience a similar bounce-back in the third quarter but warns that the pace of the recovery beyond that will depend on the course of COVID-19, policies to prevent its spread, cooperation of the public in terms of social distancing and mask wearing, and success in finding and distributing a vaccine.6 In terms of the housing market, the pandemic boosted single-family home prices in Greater Boston by 6.9 percent in July as sales rebounded from the spring7 while rents have softened somewhat, but only among luxury apartment buildings or in more expensive communities.8

Moreover, experience from prior recessions shows that Main Street does not recover as quickly as Wall Street, affecting the ability of individuals to make housing payments. The lag is even more pronounced during the current downturn given the reduced operating capacity of most businesses owing to restrictions aimed at slowing the spread of the coronavirus. Because Massachusetts had a more severe COVID-19 outbreak initially, the state’s economy was shut down earlier and more completely and began to reopen later and more slowly than most of the U.S. As a result, the number of small businesses that are open in Boston has fallen by 26 percent since January compared to a decline of only 19 percent nationwide.9

The initial severity of the pandemic and the exposure of key industries like education, healthcare, and hospitality and tourism have contributed to significantly higher levels of unemployment in the Commonwealth (11.3 percent) compared to the nation (8.4%) as of August. And although the state unemployment rate dropped significantly compared to July, most of the improvements were due to people dropping out of the labor force compared to people becoming employed. Employment is still 11.2 percent below pre-pandemic levels in the Commonwealth compared to 7.4 percent nationwide (see Figure 1).

Figure 1 – As of August, employment was still 11.2% below pre-pandemic levels in the Commonwealth compared to only 7.4% nationwide.

The Boston Metropolitan Statistical Area (MSA) lost 350,000 jobs between February and April of 2020 and only one-quarter of those jobs had been recovered as of July. Moreover, the job toll has been uneven with the rate of employment loss among high-wage (earning more than $60,000 annually) jobs in Boston being half that of all jobs combined.10 Hiring activity in Boston is still far below pre-pandemic levels with the number of job postings down 44 percent since January compared to a decline of only 21 percent nationwide.11

As with most recessions, more vulnerable populations suffer the most. Boston residents claiming unemployment insurance benefits as of July were more likely to be age 25-34, non-White, have a high school degree, and earn average wages of less than $400 per week prior to becoming unemployed (see Figure 2). Among Boston households, a higher share of Black (55 percent) and Latino (57 percent) households have experienced a loss of employment income for themselves or another household member since the start of the pandemic compared to White (49 percent) households.12

Figure 2 – As of July, unemployment insurance claimants in Boston were more likely to be age 25-34, non-white, have a high school degree, and earn average wages of less than $400 per week prior to becoming unemployed.

As of July, cities and towns with large communities of color such as Lawrence (30.9%), Revere (25.4 percent), Springfield (25.2 percent), Brockton (24.0 percent), Lynn (23.1 percent), Holyoke (23.0 percent, Chelsea (22.9 percent), and Randolph (22.6 percent) suffered even greater rates of joblessness than Boston (15.5 percent). Even among the self-employed, national data show that the challenge of keeping a small business afloat has been particularly acute for Black-owned enterprises, which were more than twice as likely to close down in the early months of the pandemic than small businesses overall. This is due to being disproportionately located in areas hit hard by the virus, having less of a financial cushion, and facing greater difficulty meeting the constraints of the emergency Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) such as the need to have an established banking relationship.13

And we are not out of the woods yet. Economists have noted several signs that economic growth has been slowing with consumer debit and credit card spending still below pre-pandemic highs and leveling off both in Boston and nationwide since August.14 The labor market also appears to be softening as fewer workers are being recalled and U.S. total initial unemployment insurance claims halting their downward trend as of September.15 A recent survey by Cornell University found that 31 percent of workers who were placed back on payrolls after being initially furloughed as a result of the pandemic report that they have been laid off a second time. Another 26 percent of those placed back on payrolls report being told by their employer that they may be laid off again. The authors note that these results were surprisingly higher for workers in states that have not been experiencing recent COVID-19 surges, relative to those in surging states.16

What does this economic outlook imply for housing stability?

Low-income households are at a particular disadvantage coming into the pandemic with little in accumulated savings or wealth to be able to weather an economic crisis. In addition, small landlords who rely on rental payments for income may exit the market, leading to higher eviction rates enacted by more impersonal corporate landlords. How will the current economic outlook impact housing stability in Greater Boston and which populations are most vulnerable to disruption?

The pandemic has only exacerbated pre-existing inequities that have contributed to the lack of housing stability in the Greater Boston region for decades. Despite small improvements over the past several years, the Brookings Institution has consistently ranked Boston among the top 10 most unequal metropolitan areas in the U.S. As of 2016, the highest-earning households (those at the 95th percentile of the city's income distribution) earned nearly 15 times what households closer to the bottom of the income spectrum earned (at the 20th percentile).17 Moreover, the divergence in incomes across the distribution is largely driven by incomes at the top growing rapidly while those at the bottom have become stagnant—such that the region’s lack of housing stability is driven by both rising housing costs as well as a lack of income growth.

While income helps families cover their current needs, wealth allows them to make investments in education, create businesses, and cover expenses when there are medical emergencies or job losses. And if the picture in terms of income inequality is stark, that of wealth inequality is starker yet—particularly along racial and ethnic lines, where the gap has widened over the past 30 years. The median net worth in the Greater Boston region was $247,500 for White people, $12,000 for Caribbean Black people, $3,020 for Puerto Ricans, $8 for non-immigrant African Americans, and $0 for Dominicans, according to a 2015 report by the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston, Duke University, and the New School.18

In Greater Boston, pre-pandemic high housing cost burdens and convergent needs for income, food, and housing assistance leave households with hard choices about which bills to pay. As of 2019, the Boston MSA had the third highest rents in the nation with the median rent for a 2-bedroom apartment in Greater Boston at $2,500, tied with Greater New York City and similar to Greater Los Angeles and San Diego.19 Affordability has been deteriorating since 2000, with nearly half of renters in Greater Boston—and an even greater share in cities like Lowell, Lawrence, Lynn, and Brockton—considered “cost burdened” since they spend 30 percent or more of their income on housing (see Figure 3). This leaves little room for low-income households to cover other expenses, especially during a pandemic. The Census Household Pulse Survey shows that among Boston area households that received a $1,200 stimulus check; just over half spent some portion on housing—second only to the share who spent their check on food.20

Figure 3 – As of 2018, nearly half of renter households in Greater Boston were cost-burdened, spending 30 percent or more of their incomes on housing, up from roughly one-third as of 2000.

So far, the majority of households have indicated that they are able to pay their rent, but there is considerable concern that this might change with state and federal supports expiring. Since the start of the pandemic, the share of households in the Boston MSA that were able to make their rental payment on time decreased from 91 percent in May to 85 percent in July,21 and national data indicates that few of these households end up making their payment even by the end of the month.22 Since the start of the pandemic, the ability of Boston area households to pay their rent on time has fallen more among non-White households than White households (see Figure 4). On average, only 9 percent of White households were not currently caught up on rent payments as of August compared to 24 percent of Asian households, 23 percent of Hispanic or Latino households, and 12 percent of Black households.

Figure 4 – As of August, non-white households in the Boston area were more likely to report not being caught up on their rent payments.

With the continued high levels of unemployment among low-income households of color and the expiration of the additional $600 per week in unemployment insurance benefits at the end of July, it’s a virtual certainty that the ability of these households to pay rent will deteriorate rapidly in the coming months. The expanded benefits had replaced a larger share of the wages for low-wage workers and, in some cases, had even provided a higher amount than the workers' pre-crisis weekly wage. For example, full-time Instacart shoppers earn $10 per hour or $400 per week. Under the traditional UI program, they would qualify for a weekly benefit of $200 per week, or 50 percent of their pre-unemployment pay. However, with the extra $600 per week under the CARES Act, they earn $800 per week or twice as much (200 percent) as their pre-unemployment pay. The intention was to ensure that those who are most likely to be hurt are able to meet basic needs during the crisis and have money to spend when the pandemic abates to help jumpstart the economy.

The expiration of the additional $600 per week in UI benefits represents not only a large drop in stimulus for the economy, but also a large drop in income for low-income households. Taking the total number of UI claimants in July and multiplying by the $600 benefit, this represents a collective loss of $280 million per week for Massachusetts residents, including a reduction of $34 million per week in Boston. Although the Commonwealth recently received approval from the Federal Emergency Management Agency to extend an additional three weeks of supplemental benefits at $300 per week, this support will also soon expire leaving households with a sharp drop in income.23 For example, we know that over one-third of UI claimants in Boston earned less than $400 per week. These individuals, like the example of the Instacart worker above, would see their UI benefits fall from $500 per week with the extra $300 in state support to only $200 per week under the traditional UI program—a 60% drop in income. And because lower-income households typically live paycheck to paycheck, this loss of income represents a direct reduction in spending.

Although the eviction moratorium was extended at both the state and national levels, the lack of rental forgiveness means that any failure to pay rent will simply accumulate over time, creating an ever-growing eviction crisis on the horizon. Municipalities with large communities of color—eviction hubs even during normal times—are again disproportionately affected during the pandemic. Even before the pandemic, communities of color such as Brockton and Lawrence and Boston neighborhoods such as Roxbury, Dorchester, and Mattapan experienced some of the area’s highest rates of eviction (see Figure 5). According to a recent study by MIT and City Life/Vida Urbana, 78% of the Boston eviction cases currently suspended by the COVID-19 moratorium were filed in majority-minority neighborhoods such as Roxbury and Dorchester as landlords moved to evict the tenants before government support or regulations were made available.24

Figure 5 – Even before the pandemic, communities of color such as Brockton and Lawrence and Boston neighborhoods such as Roxbury, Dorchester, and Mattapan experienced higher rates of eviction.

More than 5,000 suspended evictions hang over renters’ heads around the state,25 and many more new evictions are likely to be filed once the national moratorium ordered by the CDC expires at the end of the year or even sooner if it is challenged in court.26 From April to June, polling data from MassINC revealed that nearly 30 percent of Massachusetts renters missed a partial or entire rent payment, and only 21 percent of them said they were likely to be able to make up that money by the time the original state moratorium was due to end in August.27 If even just half of those who say they will be unable to catch up on rent (i.e., 10 percent of renters) are evicted when the moratorium lifts, that would mean 18,000 renter households displaced in Suffolk county alone.

In the meantime, failure to pay rent can have dire consequences for Greater Boston’s housing ecosystem. This is because smaller landlords, who account for a disproportionate share of the low-income housing market, rely on rental payments as a source of income. Due to the increase in partial rent payments, smaller landlords are having difficulty paying their rental mortgages on time. According to a national survey conducted in August by Avail, a technology and marketing platform for small landlords, 35 percent of respondents earn 50 percent or more of their income from rental properties. Among the landlords surveyed, 12 percent of them report having gone into forbearance, a provision under the CARES Act, which allows homeowners with federally-backed mortgages to temporarily suspend their payments if they are experiencing financial difficulties due to COVID-19. Another 50 percent of landlords with private mortgages are unsure if their mortgage company would even allow forbearance. Inconsistent payments from renters in the past month (18.9 percent) and concerns over renters not being able to pay rent in the future (24.9 percent) were the top reasons landlords gave for going into forbearance.28 These concerns are exacerbated for smaller-scale landlords and those who rely on the rent generated from their properties as they face the possibility of foreclosure if the ability of renters to make their payments continues to diminish.

This disruption to the housing ecosystem—especially at the low and middle price points—could increase the presence of institutional investors who are more likely to raise rents and have a higher propensity to evict tenants once any moratoria expire. A recent analysis by the Boston Area Research Initiative (BARI) finds that small landlords who own only one property account for roughly 68 percent of residential rental properties in Boston but only 34 percent of evictions, due to being much less likely to evict their tenants than landlords who own multiple properties. In contrast, large institutional landlords who own more than 20 properties account for a disproportionate share of evictions due to their much higher eviction rates (see Figure 6). Moreover, recent research from the Urban Institute shows that small rental units have the largest share of owners of color; nationally, 13 percent of owners are Black, and 15 percent are Hispanic.29 Given that COVID-19 has disproportionately affected Black and Hispanic households in terms of job loss, their greater representation both as tenants and landlords in small rental units may further exacerbate inequality if no action is taken.

Figure 6 – Small landlords account for 68 percent of rental properties in Boston but only 34 percent of evictions. In contrast, large landlords account for a disproportionate share of evictions due to higher rates of eviction.

How can we ensure an equitable recovery?

How can we ensure an equitable recovery that builds economic and financial resiliency into Greater Boston’s housing ecosystem for the long term? Despite mounting pressure from Democrats to pass a new stimulus bill that would include $500 billion in state and local aid to maintain safety net programs, including those for housing, it seems increasingly unlikely that Congress will take any action before the upcoming November election.30 And although there is likely to be some amount of funding for housing in a future COVID-19 relief package, it’s unclear when and how much aid will be available.31 Rather than wait around for Congress to ride to the rescue, there are some tangible steps that state and local policymakers can take to both ease the financial burden on renters right now while also setting the stage for a stronger housing ecosystem in the coming years.

The City of Boston and the Commonwealth have implemented a number of short-term policies and programs to assist struggling families through the immediate phase of the crisis. Yet it remains to be seen how policymakers will address the market’s underlying failures in the long term. Like any complex system, we would advocate that piecemeal efforts that address only areas of vulnerability will be inadequate to address the long-standing inequities in the low-income housing market. Policies to protect renters from disruption, support households that have trouble making payments, and make housing more affordable and accessible should be enacted in tandem to establish a more just and equitable housing market. Failing to put in place any one of these policy “legs” runs the risk of letting the naturally occurring affordable housing market collapse during the current crisis.

- Protect the most vulnerable renters from housing disruption

The blanket eviction moratorium imposed both nationally and at the state level was a necessary first response to both the public health crisis and economic disruption caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. Without such protections, individuals and families might be displaced and forced into shelters or into doubling up with friends and family. To prevent overcrowding, which would certainly increase the spread of the virus, policymakers wisely chose to take immediate action to keep tenants safely in place.

With the state eviction moratorium extended through October 17 and the recent CDC emergency order extending the national moratorium through the end of the year, however, the amount of unpaid rent will continue to snowball. This is no good for tenants, who must ultimately pay or be evicted, nor for landlords who depend on rental income to maintain their properties and/or livelihoods. Better eligibility targeting of the eviction moratorium for the long-term, such as that suggested by the CDC emergency order, could limit its use to where it’s most needed.32 Yet, such a policy should also be coupled with providing right-to-counsel for renters facing eviction from landlords who may dispute whether they qualify for the protections that have been put in place under the new CDC eligibility guidelines.

Rather than relying on such a blunt policy instrument, cities and states should give landlords and tenants the tools they need to melt the snowball of back rent and avoid eviction altogether. For example, expanding the use of mediation can help both sides come to an agreement about the tenants’ ability to pay. During recessions, landlords have an incentive to come to the table understanding that evicting the current tenant is costly and finding a replacement could be difficult. Avoiding a court hearing, especially when a tenant is unrepresented, allows the tenant more control over the outcome. Mediators attend court hearings and work with landlords and tenants before the case reaches a judge in order to identify and work toward mutually agreeable solutions. Tenants can negotiate for more time to find an affordable place to live, secure home repairs contingent upon rent payments, and clear up misunderstanding and miscommunication with landlords. With more authority over the outcome, struggling tenants are more likely to avoid housing instability and possible homelessness.

Finally, landlords themselves have a role to play in establishing best practices for preserving tenancies. For example, according to the Avail survey of small landlords in August, 38.6 percent of respondents offered deferment plans to their renters, and 21 percent of landlords reported that the use of a deferment or rental payment plan had helped them stay financially afloat during the pandemic. Among landlords who offered some type of plan, the most common option was to change the rent payment schedule (41.5 percent), followed by deferring one or more months of rent (33.2 percent), discounting on one or more months (31.3 percent), and forgiving one or more months of rent all together (13.9 percent). However, the majority of landlords who were surveyed (61.4 percent) reported they did not offer their renters any payment plans.33

- Support low-income households before they have trouble making housing payments

Since the start of the pandemic, emergency rental relief programs have sprung up across the Commonwealth to help tenants make rental payments. These include the Boston Rental Relief program and other community-based emergency rental assistance as well as the state’s Emergency Rental and Mortgage Assistance (ERMA) program, which expanded eligibility for the pre-existing Rental Assistance for Families in Transition (RAFT) program to households earning 50 to 80 percent of Area Median Income (AMI). Like the RAFT program, ERMA will provide up to $4,000 for eligible households to pay rent or mortgage payments in arrears going back to payments due April 1, 2020.34 According to the Avail survey, these supports along with other government aid or assistance had helped roughly 30 percent of renters make payments during the pandemic.35

Yet state housing programs were oversubscribed before the COVID-19 pandemic, lacking enough funding to adequately support low-income households even in good times. RAFT funding typically runs out within 9 months in any given fiscal year, and even sooner in some parts of the Commonwealth.36 In addition, over 100,000 families are on the waiting list for Section 8 housing at any point in time, with some housing authorities having chosen to close their waiting lists due to the high demand.37 Clearly, we need to think of more sustainable ways to fund emergency rental assistance programs going forward if we are going to meet the needs of low-income households in any meaningful way. In addition, emergency rental assistance programs should be designed to encourage concessions by landlords such as those discussed above to abate past due rent and discount future rent. With limited public resources and a weakening rental market, it’s simply not feasible to expect that landlords will be paid in full.

In some ways, one can think of emergency rental assistance programs as akin to the Unemployment Insurance system, which pays out benefits to individuals in the case of job loss. Rental relief programs perform a similar function by paying the tenant’s rent in the case of income loss. Similar to the UI system, one could imagine levying a small 1 percent surcharge per unit per month on large landlords with 20 or more properties that can be placed in a trust fund to support emergency rental relief. This would be equitable given that larger landlords are more likely to file an eviction petition against their tenants—similar to the higher UI tax rates that are levied on employers who are more likely to lay off their employees. Larger landlords are also more likely to make use of emergency rental relief by helping their tenants access RAFT and other programs to make payments and avoid eviction.

As noted above, the affordable housing crisis is as much an income crisis as it is a housing cost crisis. Incomes at the bottom of the income distribution have been stagnant for decades due to global competition, automation, and outsourcing. Broad income supports, such as the extra $600 per week in expanded unemployment benefits, are more efficient and effective than housing-specific supports because they allow each household to address their most critical needs while providing additional economic stimulus. Providing some basic level of income to ensure that all residents have a safe place to live in addition to adequate nutrition and health care seems like a more holistic approach than piecing together emergency rental assistance. While establishing a universal basic income program at the state level might not be feasible, expanding the Commonwealth’s Earned Income Tax Credit to provide a guaranteed income to all low-income residents earning less than $70,000 per year would be a move in that direction.38

- Make housing more affordable and accessible

Despite the laudable production goals set by the state and municipalities, it is likely that the demand for housing in the Greater Boston region will continue to outstrip supply. The region is already at a production deficit. In fact, just a little over half of the units (91,758) needed to meet the region’s housing demand as of 2018 (170,667) have been produced thus far.39

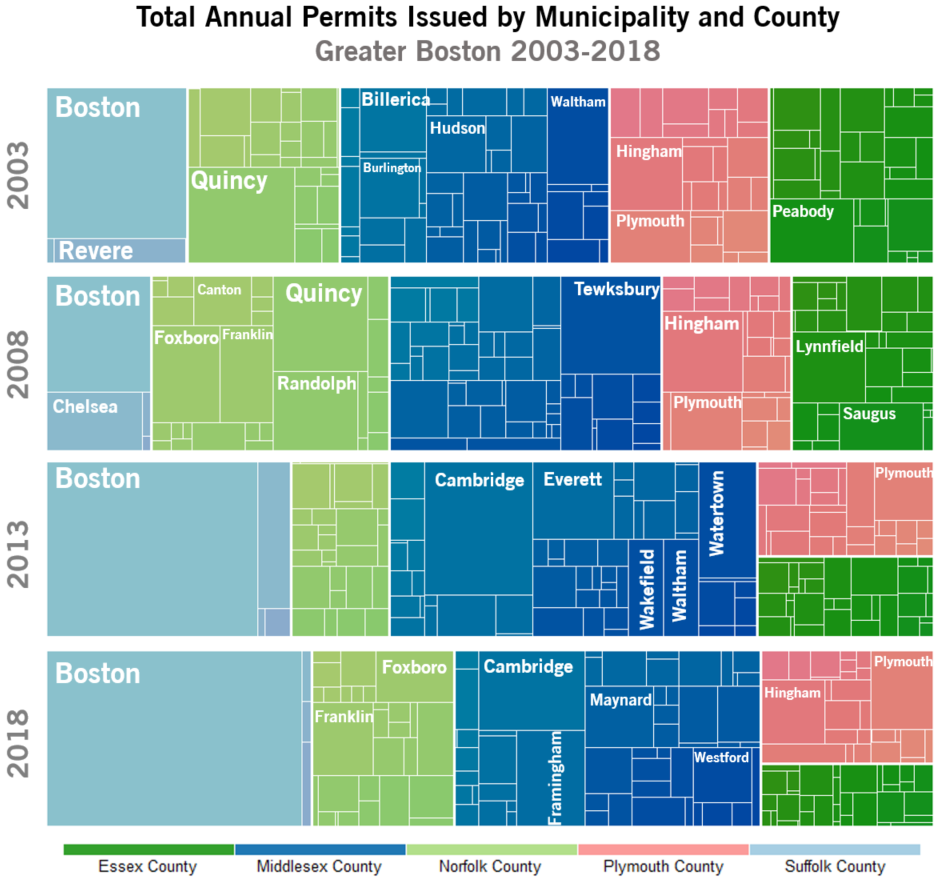

Moreover, the production of housing at the local level has been uneven across the Greater Boston region with new housing often planned in the same cities and towns that have already been producing the lion’s share of new units. For example, Boston stands out as having increased its share of new production over time since the end of the housing crisis in 2008 (see Figure 7). In contrast, suburban communities generally have not increased their contribution of housing production relative to their prior housing stock.

Figure 7 – Total housing production has been uneven across the Greater Boston region with some communities producing the lion’s share of new units.

In addition to producing enough units to reduce the upward pressure on prices, it is also necessary to build a mix of housing types to ensure that communities are open to individuals and families from both low- and moderate-income households. This kind of socioeconomic diversity within municipalities is vital for promoting vibrant communities as well as equitable access to opportunity and resources across the Greater Boston region. Although not all low- and moderate-income families will choose to locate in more affluent communities, those that wish to have access to higher-performing schools or more attractive job opportunities should be able to do so. Providing a range of housing opportunities affordable to workers of differing income levels also ensures that the region maintains a sufficient supply of labor across different skillsets.

Notably, only 27 municipalities have permitted enough multifamily housing in the past decade to account for even 5 percent of their total housing stock. This is largely due to overly restrictive zoning regulations that restrict the types of housing that are built—particularly in suburban communities. Of the 132 communities in Greater Boston that allow multifamily housing, just over half allowed it by-right and only in some circumstances. “By-right” permitting is when a development is allowed when it meets local zoning requirements without the need for a vote of approval by the planning board or another discretionary local approval.40

State policymakers are poised to pass an economic development bill that will include provisions of Governor Baker’s Housing Choice bill to help cities and suburbs build housing and end exclusionary zoning. The measure enables city councils to pass rezoning changes by a simple majority vote rather than a two-thirds supermajority vote, thereby preventing small but vocal NIMBY contingents to block new development. This is an important first step that would empower local housing advocates and strike a more reasonable balance between local land use regulation and the housing needs of Greater Boston and the Commonwealth as a whole.

Other legislative actions could expand inclusionary zoning to require a given share of new construction to be affordable by people with low to moderate incomes. These policies have been effective in creating thousands of affordable housing units in cities like Boston and Cambridge, and they mitigate the concern that the development of market-rate housing provides little direct benefit to low- and moderate-income residents in surrounding neighborhoods. The challenge for suburban cities and towns in Greater Boston is to establish inclusionary zoning requirements that allow sufficient density to make housing development economically feasible; otherwise, inclusionary zoning has the potential to worsen our housing situation by discouraging new development.

Finally, options to create pathways for ownership that transfer private housing into permanent affordability should be pursued. With more than 40,000 residents currently wait-listed for less than 15,000 affordable housing units, the city has too few affordable rental units and homes to meet the current demand. Even during the pandemic, there is a strong incentive for homeowners to sell and turn a profit, which creates substantial barriers to maintaining long-term affordability. A 2017 report from the Urban and Environmental Policy and Planning Department at Tufts University examined the barriers and opportunities for those interested in transferring their homes into affordability in the context of the Chinatown Community Land Trust (CLT). The report recommends that affordability could be improved by providing incentives for homeowners such as loans and financial assistance to homeowners in exchange for a right of first purchase or direct transfer to a CLT; outreach to city agencies, financial institutions, and homeowners about the various options for transferring; and formalization and legitimacy to pre-existing affordability mechanisms, including deed restrictions and rights to first purchase.41

Conclusion: Back to Better

For many renters in Greater Boston, threats to housing security are a persistent fact of life, even during the best of times. A significant unplanned expense or a temporary interruption to employment can mean the difference between a rent payment made and a payment missed. The relative health of the region’s labor market is crucial in maintaining a measure of housing stability.

The historic increase in joblessness brought on by the pandemic has brought us to the brink of a new rental crisis, forestalled in the short-term by a combination of payroll protections, enhanced unemployment benefits, rent subsidies, and eviction moratoriums. The most far-reaching of these programs, the $600 per week in additional federal unemployment benefits and the state moratorium on evictions, have already or will soon be expired. Communities of color are particularly at risk without these supports having been disproportionately impacted by the pandemic and suffered greater job loss—all with limited savings to draw on.

As government support fades, Greater Boston and the nation face the prospect of a significant housing dislocation that will exact its heaviest toll on income-constrained renters and the small landlords who disproportionately support the low-income housing market. Although not every payment delinquency will result in an eviction, something’s got to give. Absent any new intervention on the part of state or federal policymakers, in the coming months we will see an increase in lease renegotiations, eviction proceedings, household spending cuts, and ultimately relocations to lower quality housing stock further removed from economic opportunity.

Rather than simply put a Band-Aid on the current crisis, we have a unique opportunity to use the disruption caused by the pandemic to move “back to better” rather than “back to normal” and build a more equitable and resilient housing ecosystem. This means working simultaneously to prevent housing disruptions, provide low-income renters with income or in-kind supports, and expand the supply of affordable housing across communities to increase access to opportunity. Until we commit the resources necessary to ensure that safe and affordable housing is a basic human right, we will fail to move towards a more just and equal society.

Endnotes

[1] Wall Street Journal Economic Forecasting Survey. Accessed September 16, 2020. https://www.wsj.com/graphics/econsurvey/

[2] Modestino, A., Ziegler, C., Hopper, T., Clark, C., Munson, L., Melnik, M., Bernstein, C., & Raisz, A. Greater Boston Housing Report Card 2019: Supply, Demand and the Challenge of Local Control. The Boston Foundation, Understanding Boston Series, June 26, 2019. /news-and-insights/reports/2019/june/greater-boston-housing-report-card-2019

[3] Melnik, Mark and Abby Raisz. Racial Equity in Housing in the Time of COVID-19. #2 in the Greater Boston Housing Report Card 2020 series. July 14, 2020. /news-and-insights/reports/2020/july/greater-boston-housing-report-card-2020-race-equity-covid

[4] Imbert, Fred and Jesse Pound. Dow surges 450 points in its best day since mid-July, S&P 500 closes at another record. September 2, 2020. https://www.cnbc.com/2020/09/01/stock-futures-rise-slightly-after-strong-start-to-september.html

[5] Wall Street Journal Economic Forecasting Survey. Accessed September 16, 2020. https://www.wsj.com/graphics/econsurvey/

[6] MassBenchmarks. Massachusetts Current and Leading Economic Indices. July 30, 2020. http://www.donahue.umassp.edu/documents/IndexJun2020.pdf

[7] Despite the economy, home sales are up and home prices are breaking records in Massachusetts. http://realestate.boston.com/buying/2020/08/26/despite-economy-mass-home-sales-up-prices-break-records/#:~:text=City of Boston-,The median selling price for a single-family home rose,For condos, it was 36.

[8] One Piece of Good News: Renters Finally Have More Negotiating Power https://www.bostonmagazine.com/property/2020/08/07/lower-rents-boston-renters-deals/

[9] Opportunity Insights. Economic Tracker. Accessed September 4, 2020. https://www.tracktherecovery.org/

[10] Opportunity Insights. Economic Tracker. Accessed September 4, 2020. https://www.tracktherecovery.org/ Note: Change in employment rates, indexed to January 4-31, 2020. This series is based on payroll data from Paychex, Eamin, and Intuit.

[11] Opportunity Insights. Economic Tracker. Accessed September 16, 2020. https://www.tracktherecovery.org/ Note: Change in weekly unique job postings, indexed to January 4-31, 2020, seasonally adjusted. This series is based on data from Burning Glass Technologies.

[12] U.S. Census Bureau, Household Pulse Survey, week 12 July 16-21, 2020. https://www.census.gov/data/tables/2020/demo/hhp/hhp12.html#tablesNote: Boston is represented by the Boston-Cambridge-Newton, MA NECTA division.

<p.>[13] https://www.nytimes.com/2020/09/01/business/economy/small-businesses-coronavirus.html</p.>

[14] Source: Opportunity Insights. Economic Tracker. Accessed September 16, 2020. https://www.tracktherecovery.org/ Note: Change in average consumer debit and credit card spending, indexed to January 4-31, 2020, seasonally adjusted. This series is based on data from Affinity Solutions.

[15] https://www.dol.gov/ui/data.pdf

[16] New Cornell-JQI-RIWI Survey Shows that a Second Wave of U.S. Layoffs and Furloughs is Well Under Way https://d3n8a8pro7vhmx.cloudfront.net/prosperousamerica/pages/5561/attachments/original/1597065410/Cornell-JQI-RIWI_Poll_Report_-_Second_Wave_of_Layoffs_Well_Under_Way_-_080420_FINAL.pdf?1597065410

[18] https://www.bostonfed.org/publications/one-time-pubs/color-of-wealth.aspx

[19] Zillow Median 2-bedroom rent data, September 2019

[20] U.S. Census Bureau, Household Pulse Survey, week 12 July 16-21, 2020. https://www.census.gov/data/tables/2020/demo/hhp/hhp12.html#tablesNote: Boston is represented by the Boston-Cambridge-Newton, MA NECTA division.

[21] U.S. Census Bureau, Household Pulse Survey, week 2 May 7-12, 2020 and week 12 July 16-21, 2020. https://www.census.gov/data/tables/2020/demo/hhp/hhp12.html#tablesNote: Boston is represented by the Boston-Cambridge-Newton, MA NECTA division

[22] NMHC Rent Payment Tracker Finds 86.2 Percent of Apartment Households Paid Rent as of September 13. National Multifamily Housing Council. https://www.nmhc.org/research-insight/nmhc-rent-payment-tracker/

[24] https://www.bostonevictions.org/

[25] https://www.wbur.org/news/2020/07/06/rental-mortage-assistance-evictions-moratorium-massachusetts

[26] https://www.nytimes.com/2020/09/01/business/eviction-moratorium-order.html?campaign_id=2&emc=edit_th_20200902&instance_id=21796&nl=todaysheadlines®i_id=71239465&segment_id=37315&user_id=13c8325966316058c97b83f79c50c99e

[27] https://massinc.org/2020/06/10/making-rent-and-paying-the-mortgage/

[31] https://www.cnbc.com/2020/07/28/senate-heals-act-does-not-include-eviction-moratorium.html

[36] https://www.mlri.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/Out-in-the-Cold-FINAL.pdf

[38] /news-and-insights/press-releases/2020/july/guaranteed-income-report-20200722

[39] Greater Boston Housing Report Card 2020, forthcoming.

[40] Greater Boston Housing Report Card 2020, forthcoming.