Boston Indicators report finds Massachusetts cities among most at-risk in 2020 Census

Historically low census response rate, other factors could affect billions in Federal funds

October 24, 2018

Boston–A new report from Boston Indicators, the research arm of the Boston Foundation, finds a unique set of factors could place Massachusetts cities at a disadvantage in collecting accurate data in the 2020 United States Census, putting at risk billions of dollars in funding and affecting the political dynamics of the coming decade.

The report, Census 2020, Explained: How It Works and What’s at Stake for Massachusetts, was produced in partnership with the Massachusetts Census Equity Fund to capture both the importance of an accurate census count and the challenges facing the Census Bureau as they prepare and administer the 2020 U.S. Census count. It was released at the Foundation’s Edgerley Center for Civic Leadership Wednesday morning. The report finds that low funding and delayed preparation for the 2020 count, coupled with questions that may discourage immigrants and other groups from participating, could exacerbate issues with low return rates in many Massachusetts cities, including Boston.

“The potential undercount of Massachusetts residents has high stakes for communities from Pittsfield to Provincetown, not just because the count affects billions of dollars in Federal funding, but because it can disproportionately underestimate numbers of especially vulnerable groups, resulting in a specific loss of programs that improve their opportunities to succeed,” said Paul S. Grogan, President and CEO of the Boston Foundation.

“The Census doesn’t just serve the practical purpose of determining funding and voting districts,” said Luc Schuster, Director of Boston Indicators. “It also drives research on multiple levels that defines who we are as a nation – demographically, socially and economically. The questions we ask and don’t ask – and the responses we get and don’t get – drives decision-making in the public, nonprofit and private sectors in dozens of ways every day.”

Unfortunately, the authors note, a late start and low federal funding for the count, coupled with widely reported concerns over the introduction of citizenship-related questions to the questionnaire, run the risk of further depressing already low response rates in many Massachusetts communities.

View an online version of the report here from Boston Indicators

Some Massachusetts communities historically poor at Census response

Mail response rates to the Census have fallen steadily since 1970, resulting in a greater need for in-person outreach, and running the risk that some people and groups will be undercounted or ignored. Historically, areas with high percentages of renters, people who live in group quarters, live in non-family households, speak non-standard languages or have lower incomes and education levels have proven harder to count. Distrust of the government and its motives further depresses response rates. As a result, places like college towns and communities with larger numbers of immigrants and non-white populations tend to lag in response rates.

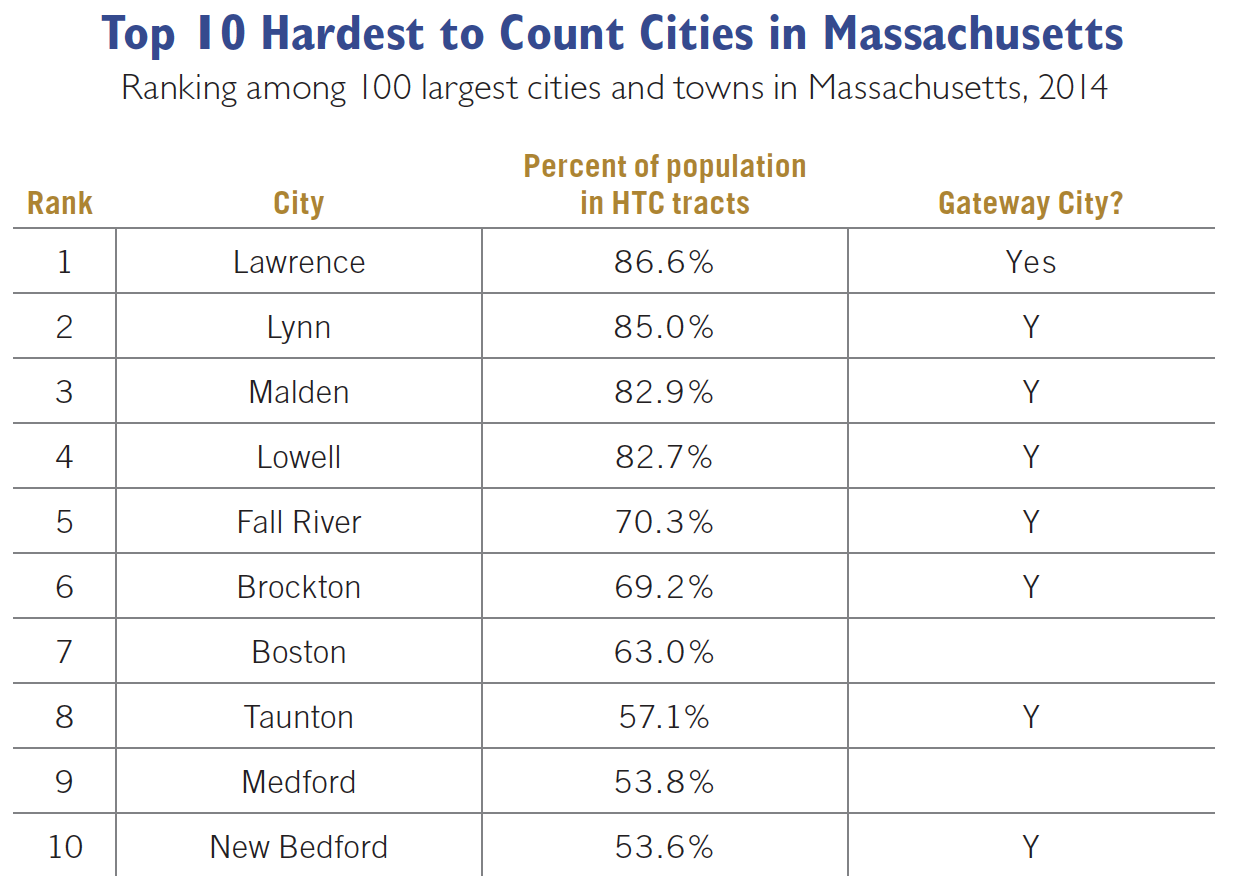

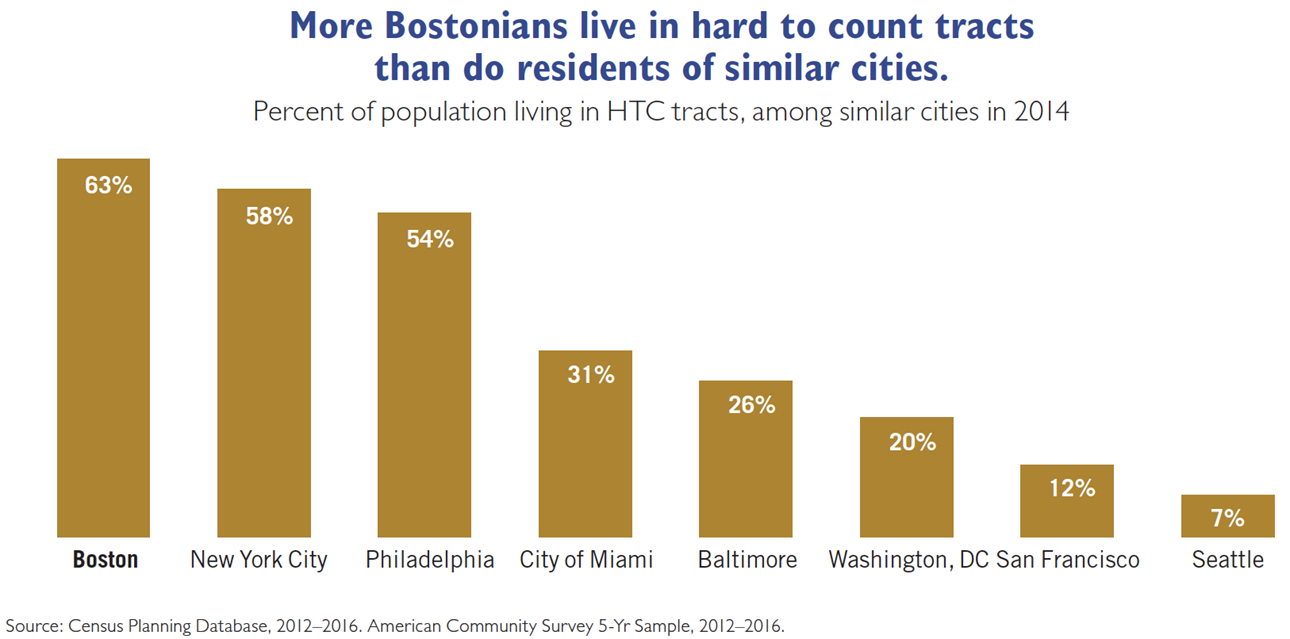

About 1-in-4 Massachusetts census tracts are designated as “hard-to-count” by researchers, defined by getting less than a 73% return rate to the mail-in survey. Over 60 percent of Boston residents live in hard-to-count tracts, as well as almost 87% of Lawrence residents and 85% of Lynn residents. In all, 11 Massachusetts cities, including 9 of the state’s Gateway Cities, have more than half of their residents in hard-to-count tracts.Compared to similar cities, Boston has a higher share of hard to count residents than New York, Philadelphia, Miami, Baltimore, Washington, DC, San Francisco or Seattle. Boston’s large share of student renters, people living in group quarters and non-family households drive the issue. The city’s percentages of foreign born and lower-income residents also likely play a role.

Billions at stake, programs affected by count accuracy

At the most basic level, researchers note, an accurate decennial Census drives whether roughly $16 billion in federal aid to Massachusetts is properly allocated to the programs and people those funds are intended to support. The count is also used by the Commonwealth, cities and towns to ensure funds are distributed properly for dozens of programs, such as, for example, funds for school districts to more effectively serve low-income students.

In an effort to improve understanding of how the Census guides Federal dollars, the report authors highlighted more than 20 programs in education, health care, housing, transportation, food and nutrition and social services where budgets are guided by Census figures.

New issues in 2020, and the role of nonprofits promoting an accurate count

Many of the issues facing the Census in 2020 have been well-publicized, most notably the addition of a question on citizenship status that has raised concern among many organizations concerned with the rights of immigrants and foreign-born citizens. In addition, Census funding for the 2020 count has lagged behind previous decades, even as the cost of reaching those who fail to respond to the mail-in request has skyrocketed. In addition, the Census Bureau is moving entirely online where it is deemed practicable, which could both improve the count in some areas and generate unexpected issues in others.

With all the concerns expressed about the Census, and the citizenship question in particular, education is being seen as a critical element of “get out the count” efforts being orchestrated by nonprofits and funders to ensure an accurate count. Advocating for, ensuring, and explaining data security and legal protections for Census respondents (public, private and government entities, including Immigration and Customs Enforcement and the courts, are prohibited from accessing personally-identifying Census data), are critical items. In addition, the Massachusetts Census Equity Fund has launched a three-year-plan to educate nonprofits and respondents about the Census, their rights, and the importance of the Census to Massachusetts economically and politically.

While the Commonwealth is highly unlikely to see any gain or loss of Congressional seats in 2020, the data is used to re-shape and balance legislative districts and the local, state and Federal levels.