Lightning in a Bottle

A film sparks candid conversations about race

TBF News Summer 2021

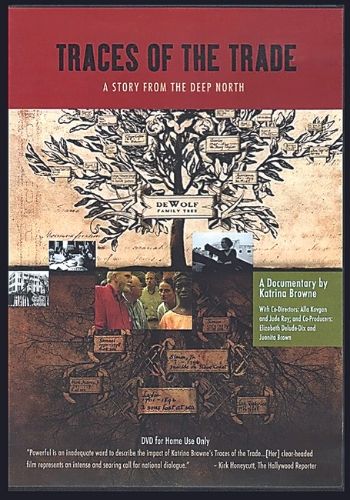

Dain and Constance Perry have a Donor Advised Fund at the Boston Foundation. Dain grew up in Charleston, South Carolina, and worked for 30 years in the financial services industry in Boston—before that serving with nonprofits that promoted criminal justice reform. Constance grew up in Boston. For more than 20 years, she managed, designed and implemented programs for at-risk youth and adults. The two have traveled across the country to conduct screenings of the film Traces of the Trade: A Story from the Deep North produced in 2008 by Katrina Browne, Dain’s cousin. The film, which premiered at Sundance and has aired on PBS, explores Dain’s ancestors role as the largest slave trading network in North America, dashing any lingering illusions that the slave trade was limited to the South. After the screenings, the Perrys facilitate conversations about the lasting wounds of slavery and racial reconciliation.

We knew we had lightning in a bottle,” says Dain Perry about the premiere of the documentary Traces of the Trade in 2008. The film, which later aired on PBS, follows Dain and nine other descendants of the DeWolf family as they retrace the steps of their ancestors’ slave trading activities, visiting the DeWolf hometown of Bristol, Rhode Island, slave forts on the coast of Ghana, and the ruins of a family plantation in Cuba. At the end of the film, they discuss the impact of the journey.

After the film premiered, Dain and his wife, Constance Perry, who is African American and a descendant of slaves, decided to show the film to faith groups, businesses, community groups and others—then facilitate conversations about the emotions and the issues it raises. Within six weeks, the power of the experience was so clear to them that they decided to retire and devote themselves to the work. They went on to lead hundreds of screenings and conversations across the country, including several sessions with Boston Foundation donors and staff. “We started 13 or 14 years ago, and we’re just about as busy now as we were then,”

says Dain.

“We’ve always had good conversations, important conversations,” explains Constance “but about five years ago, the conversations turned to being more of a lament. Our white participants said, ‘I thought we had moved further along in regards to race and racism than we have.’ Some of them had been involved in racial justice issues in the ’60s. They had protested for civil rights and gone

to trainings about dismantling racism. They were pained by the fact that they hadn’t been paying attention.

“The murder of George Floyd only intensified the discussions. I think it really shocked people who are white. African Americans and other people of color were shocked by the brutality of it, but it was nothing new—this kind of force used against people of color.”

Asked whether the topic of reparations for slavery has come up often in the discussions, Constance says that it has not. Indeed, the topic is one of the few points on which the two don’t agree. Dain prefers the word “repair,” believing that the term “reparations” has become a polarizing word for many people, who assume it means that a check will be written

to all Black people. “I have a marketing back-ground and I think there will be a colossal backlash against it.” He explains that the word “repair” comes from from the Book of Isaiah, where the term “repairing the breach” is used. “That is the intent of using that word,” he says, “Repair the damage that has been done.”

Constance responds: “Reparations is about making amends for the wrong that was done. No check or action can repair what was done. As an African American, I hear two different things. Whether the word repair is used or reparations, the good thing is that it’s being talked about. Now, it will be debated. It’s come out of the shadows.”

Dain was surprised during the interview that Constance expressed more hope about the future of race relations than he feels. “The country has taken such a giant step backwards over the last four years that it will take years to recover,” he says. Both are frustrated that those who join their screenings and conversations are “self-selecting.” In other words, they aren’t the people they really need to reach. Dain adds, “But if we can get the white folks to become more deeply involved and get the scales off of their eyes a little, then we’ve done our job.”

“What gives me a sense of hope,” says Constance, “is that in our conversations, white people are acknowledging the fact that they have just made assumptions: ‘Surely the opportunities are available for people of color to have the kind of life I have. And if people of color don’t have those things, then it must be that they haven’t worked hard enough. They haven’t studied hard enough. It’s on them.’ And now they’re saying that, ‘systemically, institutionally, things have been in my favor. There is such a thing as white privilege.’ And hearing more and more people say that gives me hope.

“When George Floyd was murdered and the Black Lives Matter movement intensified, the people who were in the streets spanned all racial and ethnic groupings. All ages and classes. We’ve never seen that before. And the fact that young people are pulling their parents and their grandparents along and saying to them, ‘You need to pay attention. You need to be involved,’ that gives me hope. If I don’t have hope, for me it’s despair. And I can’t afford to fall into that. There’s too much on the line.”

We knew we had lightning in a bottle,” says Dain Perry about the premiere of the documentary Traces of the Trade in 2008. The film, which later aired on PBS, follows Dain and nine other descendants of the DeWolf family as they retrace the steps of their ancestors’ slave trading activities, visiting the DeWolf hometown of Bristol, Rhode Island, slave forts on the coast of Ghana, and the ruins of a family plantation in Cuba. At the end of the film, they discuss the impact of the journey.

After the film premiered, Dain and his wife, Constance Perry, who is African American and a descendant of slaves, decided to show the film to faith groups, businesses, community groups and others—then facilitate conversations about the emotions and the issues it raises. Within six weeks, the power of the experience was so clear to them that they decided to retire and devote themselves to the work. They went on to lead hundreds of screenings and conversations across the country, including several sessions with Boston Foundation donors and staff. “We started 13 or 14 years ago, and we’re just about as busy now as we were then,”

says Dain.

“We’ve always had good conversations, important conversations,” explains Constance “but about five years ago, the conversations turned to being more of a lament. Our white participants said, ‘I thought we had moved further along in regards to race and racism than we have.’ Some of them had been involved in racial justice issues in the ’60s. They had protested for civil rights and gone

to trainings about dismantling racism. They were pained by the fact that they hadn’t been paying attention.

“The murder of George Floyd only intensified the discussions. I think it really shocked people who are white. African Americans and other people of color were shocked by the brutality of it, but it was nothing new—this kind of force used against people of color.”

Asked whether the topic of reparations for slavery has come up often in the discussions, Constance says that it has not. Indeed, the topic is one of the few points on which the two don’t agree. Dain prefers the word “repair,” believing that the term “reparations” has become a polarizing word for many people, who assume it means that a check will be written

to all Black people. “I have a marketing back-ground and I think there will be a colossal backlash against it.” He explains that the word “repair” comes from from the Book of Isaiah, where the term “repairing the breach” is used. “That is the intent of using that word,” he says, “Repair the damage that has been done.”

Constance responds: “Reparations is about making amends for the wrong that was done. No check or action can repair what was done. As an African American, I hear two different things. Whether the word repair is used or reparations, the good thing is that it’s being talked about. Now, it will be debated. It’s come out of the shadows.”

Dain was surprised during the interview that Constance expressed more hope about the future of race relations than he feels. “The country has taken such a giant step backwards over the last four years that it will take years to recover,” he says. Both are frustrated that those who join their screenings and conversations are “self-selecting.” In other words, they aren’t the people they really need to reach. Dain adds, “But if we can get the white folks to become more deeply involved and get the scales off of their eyes a little, then we’ve done our job.”

“What gives me a sense of hope,” says Constance, “is that in our conversations, white people are acknowledging the fact that they have just made assumptions: ‘Surely the opportunities are available for people of color to have the kind of life I have. And if people of color don’t have those things, then it must be that they haven’t worked hard enough. They haven’t studied hard enough. It’s on them.’ And now they’re saying that, ‘systemically, institutionally, things have been in my favor. There is such a thing as white privilege.’ And hearing more and more people say that gives me hope.

“When George Floyd was murdered and the Black Lives Matter movement intensified, the people who were in the streets spanned all racial and ethnic groupings. All ages and classes. We’ve never seen that before. And the fact that young people are pulling their parents and their grandparents along and saying to them, ‘You need to pay attention. You need to be involved,’ that gives me hope. If I don’t have hope, for me it’s despair. And I can’t afford to fall into that. There’s too much on the line.”